Of Silence and Oranges

Perhaps it is time to talk about the desert. Especially since Kuwait is a hard place for love.

I had come back from the Northern Kuwaiti desert a week ago and was still hearing the vacuum of silence that was out there in all the corners of the city I found myself in.

The road that stretches up through the northern desert toward Iraq is a long and straight one, broken only by endless chain link fencing to keep the camels off of the highway and power lines taking electricity to the Bedouin tents. I had driven out there to take a look at it, meet and interview some camel herders if I could, and stand beneath the massive desert sky. The car had spun swirls of sand and dust upward as I pulled it off the highway and into the sand, parking it next to a dead camel. The camel looked like a deflated burlap sack, half buried in a pile of sand and loose trash. Picture worthy.

The car door seemed to boom when I closed it, unnatural and heavy. I opened and shut it again thinking that perhaps the hinges needed oiling. Same sound. Then I noticed the silence.

It yawned around me, complete and thick. No insects buzzing, no tree leaves to shake in the wind, the highway too far off to hear the cars, no camels, no cell phones or the DVD hawkers that stalk my apartment barking for the sale. Pure and absolute nothing, silence defined, the death of sound. My eyes moved around the horizon, looking for life, for sound, for anything half human, and found nothing. Just myself, the sky and the silence. The silence was not oppressive, just thick and it seemed to take the sound of my own breathing away, all sounds — if there were any — swallowed up by this massive whole. I walked around just looking and thinking and feeling the silence like one of those hollow spaces in the heart, spaces reserved for loss.

When I did end up finding the camel herders, my yelled greeting to them from the distance sounded so odd, so foreign, that I felt awkward opening my mouth again to tell them what I wanted. Sound has no place out there.

Now, a week later, that silence kept opening itself up where I least expected it. Waiting for the butcher to cut a lamb shoulder for me I had heard it again, in between the sharp thump of his knife against the cutting board and the upswing of his cutting arm. It had appeared when I saw a veiled beggar woman sitting cross-legged in the great and loud second-hand souk. And then, near dawn in a litter strewn backstreet of Kuwait City, I heard it again, strewn between the words coming out of Lei’s mouth.

Lei is a Chinese whore who lives in the apartment building behind mine. I had seen her walking around the neighborhood, but didn’t know she fucked for a living until I saw her get out of a cab after which the driver paid her. The next time I saw her was at the bottom of a low and blue moment I was having, and I used her to fill the void. After that I’d have her up every so often, but never routinely, and we’d work out our respective problems quickly, without passion or the English language. She’d stay for a cup of Darjeeling tea when it was over, and would then walk out, always a swath of black hair falling across her forehead.

I gave her up after I had seen her in my elevator with the sixty-year-old guidance counselor who lives above me. He has a darting way of speaking and never looks you in the eye when he talks, and I didn’t like the fact that she’d have to deal with that while they fucked. But she kept coming for tea when she was done with him.

We’d sit in the dying light of the day and talk about small things, about life in the city, and I’d get her to tell me her war stories. About the cab drivers and the policemen, the way she’d throw her jeans across the floor and the way one man would hand her the money, crumpled and with his head down, his wife asleep next door. Her eyes never filled with life and always held the beaten and sad look a whore gets when she’s been at it too long and for too little. A beaten and sad look that told and taught me more about men’s hearts than any dark corner of the street or any crushed cigarette butt in an ashtray with lipstick dried on the end. A look that had crossed thousands of miles to come to the desert to work as a maid to support her kids at home, only to find her new home a small jail of servitude and beatings. A look that had carried itself out of the front door of that home and into her new apartment, a rent she could pay more easily with fucking than through housekeeping.

Sometimes when I was killing time by walking the neighborhood, I’d stop by her building and buzz up to see if she was there. If she was she’d come downstairs, and we’d sit in the foyer of the building on the stiff tan couches that were there, share cigarettes and an orange that she’d bring down. She always had the best oranges.

After the desert I had felt that low and blue streak again and had been trying to get rid of it by walking those back streets and forgetting. It hadn’t been working so I had rung up Lei. She came down with an orange.

It was late and she’d been working all night — rent coming up in a week. She sat in a pair of sweatpants with a tiny hole in the left knee, a piece of torn cotton dangling across the hole. Her right leg was tucked beneath the left, her bare foot just hanging above the tile floor, hesitant and swinging. That sweep of black hair fell across her forehead. She peeled the orange slowly, using her thumbnail to pull the peel back. Her cigarette burned slowly in the ashtray, and I stared out of the big windows at the dawn traffic just starting up.

“I bought this orange this morning,” she said.

I turned and looked at her.

She smiled with the corner of her mouth.

I got the sense she was trying to talk to forget, and I didn’t have much to say.

“It might not be ripe,” she said.

“You always have the best oranges.”

“When I can get them,” she said.

She leaned forward slowly and passed me a half. I bit in, sucking out the juice. It was ripe and good and had a sharpness to it.

“I had a cabbie tonight. He had eight toes,” she said, speaking slowly, neither in a rush nor worried, just tired. “His shoes were worn in all the wrong places because of it. He limped into bed.”

Then she stopped speaking and reached for her cigarette. It was then that the desert silence came back to me.

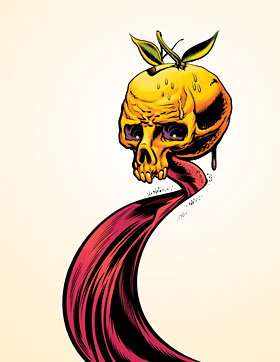

When she started talking about the cab driver again I could hear the silence in between the words. It was as if her words were falling out of those dead and silent spaces, the spaces where sound seems so odd. The words separated from her story, appearing as single whole notes. They didn’t carry much weight or feel, not nearly as much as the silence between them. A silence that stretched back into a bed with an eight-toed cabbie, and past that to a maid’s uniform, and beyond that to a village in the Yunan where she had first learned to smoke. A silence that carried with it an unending procession of hopes and the fears of the night, of the soft tattoo of the struggle that took the place of living. Of sand and a mountain and the long hard breeze in between. Of the space between the grunts of a fuck and the death of sound. Of the short distance between flesh and dead bone.

The desert silence is just the silence of man’s heart reflected outward. The silence that man carries secretly and bears when he can’t forget himself. A forgetting that she and I had tried to do over fucking and oranges, and now couldn’t do without.