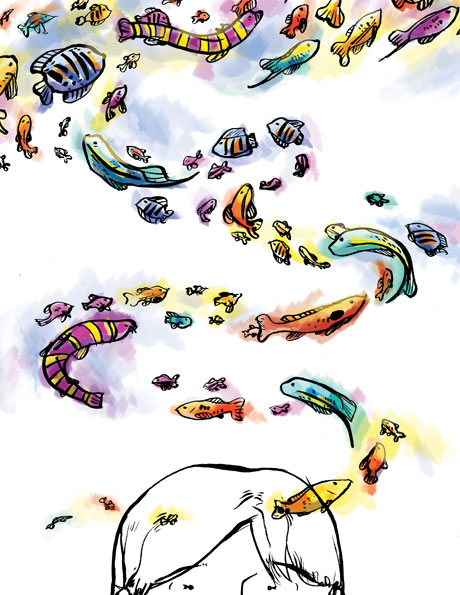

An aquarist is a sort of God. And at first, I was a loving deity.

Memories of a Fickle God

As sixth grade waned into summer vacation in 1971, I had a dozen aquariums to keep clean and sparkling and filled with life: three upstairs in my room, the rest down in the basement.

I had guppies and swordtails and platys, tetras and gouramis and barbs. I had live worms in the fridge – clumps of wriggling brown tubifex in one-inch plastic containers, awaiting feeding time. (Ah, my forbearing parents.) And there was algae, algae everywhere.

The cichlids in the 29-gallon downstairs had spawned; their eggs were hatching, filling the top of one tank with the tiniest fry – little eye dots attached to transparent-speck bodies. These tiny sproutlings of life would fast become food for bigger fish – Mom and Pop among them – unless immediately sequestered in foster care.

Nature is red in tooth and claw, and fin, too: the child aquarist learns this up close. There was goodness, also, of course. As with the mouth-breeders: they’d hatch their eggs in Mama’s mouth. The fry would nestle safely – no eating their young here! – until grown big enough to survive on their own.

And there were miracles. Upstairs, the community tank – the urban melting pot of my aquatic universe, where multiple species coexisted in relative harmony – had recently experienced its very own resurrection.

King Dojo, my kuhli loach, had disappeared. This was not unusual; these loaches are wriggly scavengers, snakelike but clownish, with narrow bands of orange on a brown background and comical barbels on their faces, and they hang out under rocks or bury themselves in gravel, so you don’t worry when you don’t see them for a few days. But mine had been gone for so long that I took him for dead. One day I was cleaning a filter that had been off the tank for a couple of days, and noticed my loach nestled in the bottom under a damp piece of glass wool. Poor desiccated dead thing, I thought. But when I put the filter back in the water, King Dojo swam off as though nothing had happened.

What do you do to commemorate such an unlikely blessing? I composed a cantata on the piano in honor of the restored monarch.

I was always drawing maps and writing histories and assembling dynastic charts for my fish; they were my very own Middle Earth, requiring just a little care and Tetra-Min to animate my epic narratives. I loved these worlds that I presided over. For a while.

Two years or so, my enthusiasm lasted. When it began to wane, so too did the quality of life for my charges. The algae went unscraped. The live feedings grew sparse. Over time, my visits to the basement tanks dwindled, and they sank into brown neglect. Fish died, one by one, as fish will do, and I did not replace them.

I’d become a bored God.

I abandoned my fish, not without guilt, as I moved on to other, drier preoccupations: first, the history of the American Civil War, then games – in that electronic dark age, we played our battles with die-cut cardboard units and hexagon-gridded maps. Later, it was Diplomacy, and Dungeons & Dragons, and publishing mimeographed magazines about Diplomacy, and Dungeons & Dragons.

The power of each new interest almost entirely obliterated its predecessor. I was a serial geek: one passion at a time, each one a buffer for my surfeit of adolescent obsessive capacity, absorbing all the insecurity of teenagerhood in a warm, welcoming, bottomless pool of fascination.

Later, as puberty crested in waves of loneliness and doubt and desperation for romance or sex or just any sort of girlfriendly experience, all of which seemed entirely unattainable at the time, I clung to my knowledge that, whatever happened – even If I’d been fated to a lifetime of isolation – a haven always awaited me in my obsessions.

This got me through to the other side of the desperation of my age. I knew I could always build a world for myself, and that world would welcome me. I would just have to learn not to abandon it.

![]()

Scott Rosenberg is a writer in Berkeley and a geek for whatever he is writing about at the moment because otherwise writing is just too hard. wordyard.com

Mal Jones is an artist in Alexandria and is a geek for comics because they’re awesome, yeah! maljones.com